Gary Gershony, MD, Interventional Cardiologist, presents an overview of Stable Ischemic Heart Disease (SIHD) from its definition to treatment options. The presentation examines Definition, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management, OMT vs. Revascularization, PCI vs. CABG surgery, Guidelines and Appropriate Use Criteria (AUC).

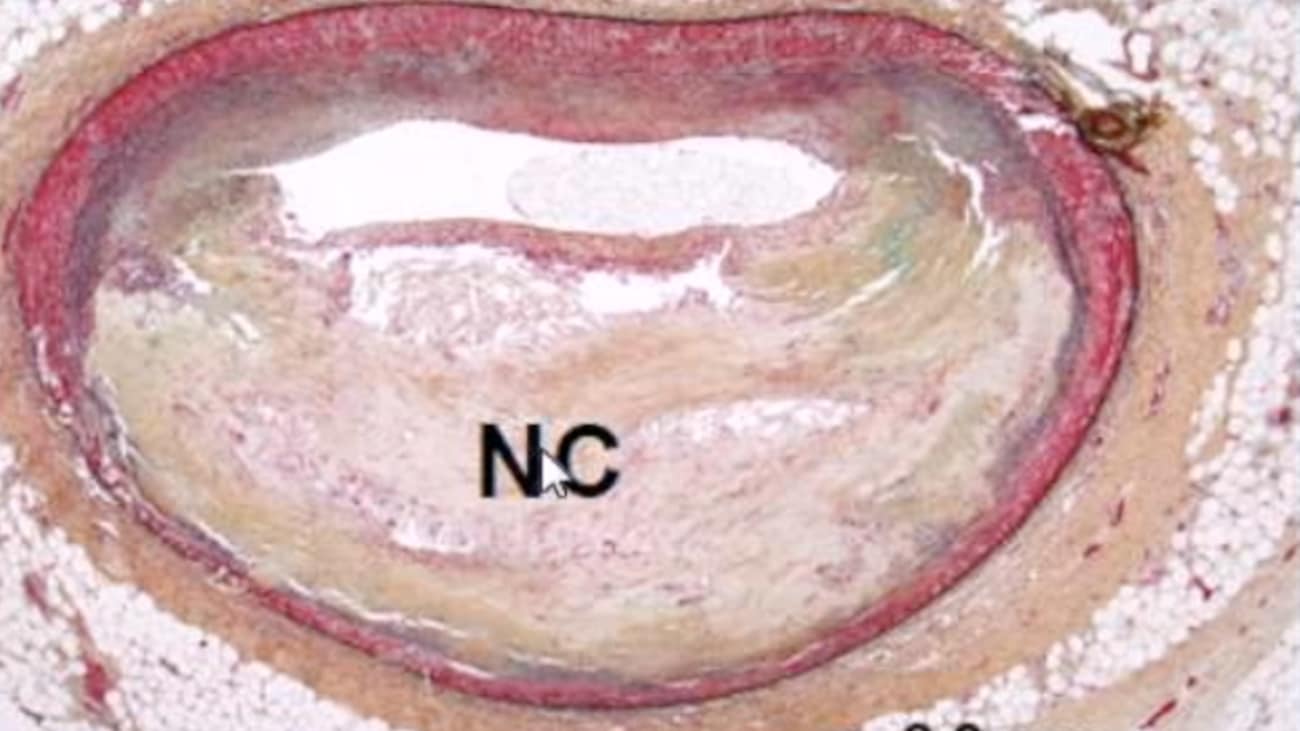

SPEAKER 1: Welcome to our monthly cardiovascular grand round series. You may know that we had a gap last month, and we did not have cardiovascular grand rounds. But we're back on track and look forward to very interesting presentations over the next six to 12 months. I had the honor today of being the lecturer for grand rounds, and the topic of my presentation is a very broad and complex topic that I hope to be able to summarize in a succinct and meaningful way for you over the next 45 or 50 minutes. And the topic is stable ischemic heart disease. This is my statement of conflict. I do not have any conflicts associated with this presentation. So we are going to review stable ischemic heart disease according to this outline. We'll talk a little bit about what does it really mean, the pathophysiology of the disease, how we establish diagnosis, management, optimal medical therapy-- which is now generally referred to as guideline-directed medical therapy or GDMT, you'll see that in the literature, versus different revascularization options-- the role of percutaneous coronary intervention versus bypass surgery, and finally looking at the more recent guidelines and appropriate use criteria published by the name societies-- including the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association. This is a famous slide of Frank Netter, a well-known medical Illustrator, and you can see what we used to think of as the typical candidate for stable ischemic heart disease. It has become really a equal opportunity afflictor. It doesn't just afflict the typical north eastern, 50 year old, tightly-wound salesman, but many other individuals of many other backgrounds. And in this particular individual classic presentation, a three month history of stable exertional angina. And you can see, this gentleman came out of a restaurant, probably had a big steak, in it's cold weather-- all the things that we know can, certainly, provoke symptoms of angina. He's currently on no medications. What should be the approach to management? And that's what we're going to try to address with this enormous amount of data that has been accumulated over the last few decades. Perspective of coronary artery disease is very broad, and it makes it difficult to answer that question with a specific approach. As you can see here, depending on the degree of coronary artery disease, even with stable angina, there is quite a variance in the outcome-- whether it's death, MI, or other risks. And as we go from the stable angina syndromes to acute coronary syndromes and stymie further changes or increases in the outcomes, in the adverse outcomes. So when we talked about stable coronary artery disease, it can be confusing. What does it generally mean? Stable angina encompasses a range of patient and disease characteristics. And remarkably enough, when we talk about stable angina, we often include patients that don't actually have symptoms of chest pain or angina, but that do have other criteria that establishes that they myocardial ischemia. Not only are the symptoms of stable angina diverse, but as I've shown you in the prior slide, so is the prognosis. Let's shift gears a little bit now and you look at the pathophysiology, starting with molecular and cellular mechanisms. This is a very complicated and busy slide, and I show it to you, mainly, to indicate how complex this disease is at a cellular and molecular level. And here you can see, we've learned in the last decade or two the important role of inflammation, and cells that are involved with information-- in this case the macrophage as it goes through apoptosis or death and involved very much with the expansion of a very important component of the plaque in coronary arteries, the necrotic core. We also learned that there are other important cellular mechanisms including enzymes and matrix [INAUDIBLE] proteinases. These are enzymes that are involved with breaking down certain part of the structure of the plaque, and it may lead to the plaque becoming more vulnerable and rupturing at the time of an acute coronary event. More recently, a modified classification of vascular sclerosis was proposed by Renu Virmani, the modified AHA classification. She's a very well-known and prominent cardiovascular pathologist, and she has gone through this classification with the earliest days of the intimal thickening that can occur very early in life. We've seen this even in studies that you may be aware of, such as a study of US airmen, many years ago, that demonstrated the beginnings of atherosclerosis, even in our late teens and early 20s-- followed by intimal xanthomas, pathological intimal thickening-- also generally referred to by the acronym, PIT-- fibrous cap atheroma. And all the [INAUDIBLE] thin cap fibrousatheromas. These are generally considered the most risky of the plaques, the so-called vulnerable plaques. And when that occurs, the patient may become more prone to the next phase, which is the plaque actually losing its integrity, either through rupture or erosion. And then the patient may experience one of the serious acute coromary syndromes as a result of this. Here you see these types of plaques demonstrated in a schematic representation. On the far left, you see the earliest intimal thickening, all the way through to the so-called thin cap fibroatheroma-- also generally referred to by the acronym, TCFA. And in the disease state that we're talking about today, chronic or stable ischemic heart disease, the pathognomonic type of plaque that we see is this more mature atherosclerotic [INAUDIBLE] plaque that has a thick fibrous plaque, a relatively small necrotic core and may or may not have some calcification. Contrast that with the more dangerous, thin cap fibroatheroma, or vulnerable plaque, that often has a large necrotic core. You can see depicted here, a very thin cap, usually less than 65 microns. And the cap is often infiltrated by inflammatory cells. And this is the kind of plaque that often will lead to rupture and an acute coronary syndrome. Here you see, again from work by Renu Virmani, the types of coronary thrombosis that we see. We used to think that plaque ruptured was a universal way in which the plaque actually lead coronary thrombosis. We now know this is more typical in men of middle age. But in women, plaque erosion tends to be a more common form of the predecessor to coronary thrombosis. And in the elderly, a calcified nodule tends to be the more likely pathophysiologic predecessor to acute coronary thrombosis. We've also learned some other very important things about where these plaques actually occur. The spin cap fibroatheromas, or TCFAs, they're either a lead to coronary thrombosis or a heal and then cause plaque regression-- tend to be clustered, predominantly, in the proximal portion of vessels and in the left [INAUDIBLE] descending coronary artery, which is unfortunate, of course, because we know that tends to be a more important artery afflicted by atherosclerosis, leading to more dire consequences for patients. And as I mentioned, in addition to the location, these plaques often don't have the type of severity of narrowing of the artery that we would think of. So the likelihood of a plaque rupturing and causing a serious life-threatening, adverse event, and the likelihood of a plaque causing stable angina, often is a dichotomous finding. What I mean by that is the plaques that are more likely to lead to a [INAUDIBLE] or a life-threatening event tend to be less severe-- actually lesions that we deem to be not severe enough to warrant revascularization-- less than 50% in severity, as you see here in this summary of different studies. A very important study was published several years ago in the New England Journal of Medicine-- this was called the PROSPECT Trial. And given the advent of newer imaging technologies that allow us actually do, if you will, in vivo [INAUDIBLE] pathology, namely intervascular ultrasound-- particularly with a type of technology called virtual histology. A number of patients were enrolled in this trial, about 700 or so, and they were followed for several years. All of these patients at baseline when they presented with an acute coronary syndrome had intervascular ultrasound with this type of virtual histology. And these findings that you see here on ultrasound virtual histology do correlate very well with histopathologic findings. So these whitish type of images reflect calcification, the red-- more of a lipid core, and you can get a sense of the camp overlying this plaque is very thin. And in the PROSPECT trial, they attempted to define these type of plaques and follow them along and see how patients did clinically. And what they found was when they identified plaques and in fact had features of thin cap fibroatheroma and also were able to measure the amount of narrowing minimal luminal area and the amount of plaque burden. These were extremely powerful predictors of the patient subsequently having events. Here you see, on this slide shown, in patients who had been capped by fibroatheroma, that we have shown really only in pathological series prior to this as being correlated with acute coronary syndrome. But if they had it, they were far more likely, statistically, to have an acute coronary event or a MACE event over the subsequent three to four years of follow up, as compared to those who did not have a thin cap fiberatheroma. And if you go all the way through to the final part of the graph, the far right, in patients who have all of the most serious features-- namely a thin cap fiberatheroma, a plaque burden-- meaning a large, bulky plaque of over 70% of the lumen of the vessel, and a minimal luminal area that was less than four millimeters squared. These patients were at very high risk of a major adverse cardiovascular event over the ensuing three to four years-- 17.2% versus those who did not, where it was only 1.8%-- almost a tenfold increase in risk. So very, very strong support in corroboration of what we have speculated from prior only histopathologic studies. So summarizing what I've shown you about the underlying pathophysiology of atherosclerosis-- first of all, it doesn't tend to occur in specific spots. We've already talked about it having a predilection for proximal parts of the vessel, and particularly in branch points where there are low shear force areas. Risk factors certainly do influence the type of plaque morphology and should be treated aggressively. There are three main causes of thrombosis-- plaque rupture, which is the most common and is almost the universal cause in middle age men. Plaque erosion-- more common in women and calcified nodules-- more common in the very elderly patients who present with acute coronary syndromes. Vulnerable plaques, which we now generally consider to be synonymous with thin cap fibroatheromas, or TCFAs, are the likely precursor lesions of rupture. Asymptomatic ruptures are probably the cause of rapid plaque regression, in which patients don't actually end up with an occlusive thrombosis, but in which they have a silent rupture. And plaque hemorrhage may also be an important contributor to the enlargement of the necrotic core and may influence the development of symptomatic disease. I'm going to shift gears now and talk about the diagnosis. And this slide summarizes the way in which we should approach these patients. So still the mainstay of establishing the diagnosis of a stable ischemic heart disease should be the clinical examination. Even with all of our very advanced imaging technologies, there's no replacement for any excellent clinical exam-- in particular, the history, the physical examination is often not that revealing. Nevertheless, a clinical examination is really critically important for helping us move forward with selection of the appropriate testing and then management of the patient. And then you can see the listing of the different type of test that we use, all the way from the most simple treadmill stress test to invasive coronary angiography. This slide is a little bit busy, but it's a very important slide-- because I think many of us forget that the tests that we use have different accuracies in terms of establishing the diagnosis of ischemic heart disease. And remember, most of these tests, with the exception of, for example, coronary CTA and invasive coronary angiography, most of these tests really are not establishing the severity, or anatomic severity, of stenosis. They are really looking to identify whether or not the patient is having ischemia. These are two entirely different things that we are looking at. And as we learned from the prior slide in the presentation, there are many patients who may have lesions that are not severe enough, or neurons that are not severe enough, to provoke ischemia on any of these tests. Yet, they may be the kind of lesions that put the patients at great risk for a lethal or very serious event and plaque rupture. And so I think that we have to understand that a negative test, if you will, or the absence of an abnormal finding on many of these tests that are looking for ischemia doesn't necessarily mean that the patient doesn't have very serious atherosclerotic disease that may lead to an adverse event. But again, just to look at these, you can see there's a wide variability in the sensitivity and specificity of the test. I would say, as I reflected on the slide preparing the presentation, I was gratified to see that in our own noninvasive laboratory here, we tend to use a test that has had the best established sensitivity specificity, namely stress echocardiography-- which you can see here has sensitivity and specificity results in the 80% to 90% range, and pharmacologic nuclear profusion stress testing, which similarly has those degrees of sensitivities and specificity. So I'm going to move now to the management of st. stable ischemic heart disease, and most of the rest of the presentation is going to be related to this topic. And this summarizes the approach that we should have to all patients, considering the three pillars, if you will, of the management of stable ischemic heart disease. Most importantly, and the treatment arm that should be applied to all patients, whether or not we consider revascularization, is optimal medical therapy. Now more commonly referred to as guideline-directed medical therapy. And optimal medical therapy can further be subdivided into lifestyle interventions, as well as pharmacology, and we'll talk a little bit more about that. Percutaneous Coronary intervention-- since its initial start in 1977 with the first balloon angioplasty performed by, at that time, an obscure and now quite famous interventional cardiologist, Andreas Gruentzig at University Hospital in Zurich-- has grown to encompass a very large field with many different tools in the armamentarium. And when I started, believe it or not-- although I'm sure that all the gray hair will support this-- all we had were the lowly simple, conventional balloons. And that's all I actually had in the early years of my practice. And we've come a long way, if you will, over the ensuing 20 or 30 years, and we've participated here at John Muir, in our research program, evaluating some of the latest and greatest newest stents-- most recently, biodegradable vascular scalpels or the absorp stent. And as yet, we in the US have not had an opportunity to test out drug-coated balloons, although many of these are now already available in many countries outside the US. And last, but certainly not least, what used to be the mainstay of treatment of patients with advanced coronary artery disease who had failed medical management is coronary artery bypass surgery. And even here, there have been tremendous advances that we need to be aware of. The important role of arterial versus venous conduits, and, in general, recent randomized trials suggesting the more arterial conduits we can use, the better. There was a lot of interest a number of years ago in on versus off-pump surgery, although that interest has waned somewhat along with MIDCAB as well. And more recently, although not shown on this slide, there's been an interest in combining approaches-- so-called hybrid procedures in patients with complex diseases or patients who are not good candidates for a more conventional bypass surgery procedure, where they will have some of the vessels managed-- perhaps the most important vessel, the LED managed, with an [INAUDIBLE] already graphed in a so-called [INAUDIBLE] type of procedure. And other vessels that perhaps are less important or less accessible in this approach could be treated with a percutaneous coronary interventional approach, either at the same time or sequentially. Shifting now to optimal medical therapy, what is available to us? And you can see here that this too has developed remarkably over the last 10 to 20 years. And when I started practicing almost 30 years ago, we really had very limited alternatives in terms of what we could offer patients. And we know now, from many studies, that quite a few of these agents not only can improve the patient's quality of life, but also their longevity. So whether it's antiplatelet therapies, aspirin being an important mainstay in any patients, or the new, not so new any more, P2Y12 inhibitors from ticlopidine in the early days now, all the way to drugs like [INAUDIBLE] and [INAUDIBLE]. We know that the Statin drugs have been extremely important in terms of improving the outcome for many of our patients. Not listed here, one of the newer anti-lipid agents, the PCSK9 drugs-- which it still remains somewhat controversial in terms of how broadly these drugs should be used. But clearly a very important new class of drug to treat patients that are resistant to Statin drugs. ACE inhibitors and angiotension receptor blockers have an important role to play as well in secondary prevention of stable ischemic and perhaps even primary prevention of stable ischemic heart disease. Beta blockers we know play a very important role, particularly in patients who have demonstrable ischemia or a prior [INAUDIBLE] infarction. More recent studies suggest that perhaps we're using beta blockers in situations that we don't need to any more. A recent study in the last month in the journal American College of Cardiology suggests that many of our patients that have atherosclerotic disease and have PCIs really don't benefit by beta-blockers after. And this is something that I think we need to look at in terms of our clinical pathways, because many of us, and even governmental agencies, expect these patients to go home on beta-blockers. But some of the more recent data suggests that a lot of our patients may in fact that not get any benefit from this. And there are certainly side effects from these drugs. Calcium channel blockers tend to be more of a secondary type of drug and more to treat risk factors such as hypertension. Long acting nitrates are not used as often as they used to be, but often they'd be very useful in terms of improving the patient's symptoms. And then in patients who are resistant, or continue to have anti-ischemic symptoms, or that they're hemodynamics, they need blood pressure-- don't allow them to have optimal doses of some of the other drugs that I already mentioned. Ranolazine can play an important role in terms of alleviating symptoms. As I mentioned before, lifestyle is critically important and should be applied in all patients. And then in other countries, there are other technologies that have been utilized, including EECP, which you may be aware of-- enhanced external counterpulsation. For lack of a better description, this is really a noninvasive intra-aortic balloon-pump. And in other countries in which there hasn't been as much use of invasive ways of treating patients to fail medical therapy, this has been utilized. There have been a number of randomized trials that have strongly supported the efficacy in alleviating symptoms of myocardial ischemia. And it's frequently used in Asian countries, including China. This slide summarizes a recent summary from the American Heart Association on goals, risk-factor goals that we should try to achieve in these patients as part of the holistic management of the disease. One of my favorite studies was published a number of years ago in the New England Journal of Medicine. This is the PREDIMED diet. You may be familiar with this, but for those of you that are foodies, this was one of the greatest studies, because it showed that if you really do enjoy a Mediterranean diet, a true Mediterranean diet-- the kind of diet that is part of the normal cuisine in countries that surround the Mediterranean if you will, the countries that we all think are very attractive to visit-- whether it's Spain or Italy or what have you. If you actually abide by that diet, it showed in this very well-conducted randomized trial with three arms that you actually have a very profound effect on reducing major adverse cardiovascular events. So this study was roughly 7,500 patients who are at high risk for cardiovascular disease. Half of them have diabetes [INAUDIBLE], and they were randomized to one of three diets. The study was conducted mainly in Spain. So one diet was a Mediterranean diet, the classic Mediterranean diet-- so a lot of legumes, a lot of vegetables, not a lot of red meat. And one arm was supplemented with extra virgin olive oil. One arm was a Mediterranean diet supplemented with mixed nuts. And the third was the usual HA prudent diet, if you will, the kind that we've advocated for many, many years in this country. The primary endpoint was the kind of endpoint we care about-- death, MI, and myocardial infarction. And I'll draw your attention to the graph on the far right, Kaplan Meier Survival Curve. And what you see here that the combined endpoint of death stroke and myocardial infarction was highly statistically, significantly reduced in the Mediterranean diet arms, in the two arms, as compared to the control diet up to five years-- perhaps, and in fact, better than we've seen with almost any other pharmacologic intervention. This is one of the few things in life where it tastes better, and it's also good for you. So I think that as we go forward, we need to understand that there are many things we can do to improve the outcome for our patients. This study, the Teresa trial, was an important trial showing the role of Ranolazine as an alternative drug in patients who have continued angina, despite the stepped approach that I showed on a prior slide. And the important endpoints of this trial were angina frequency on treatment. And importantly, what they showed was in the patients on Ranolazine in this randomized trial, there was a significant reduction, and probably clinically meaningful reduction, in the angina frequency in the Ranolazine group, as compared to the placebo group-- and a reduction in the amount of sub-luminal nitroglycerin that the patient required. So why do we revascularize in stable ischemic heart disease? Well, we do that to improve angina and quality of life for sure. That's a very important thing, and we should never forget that. We hope to improve survival, not in all patients. And sometimes, maybe the majority of the time in some cases and it shouldn't be that way, we may do it to meet patient's expectations. If you tell a patient, in my career, I can remember often telling patients well, you've got a moderate stenosis in an artery. It's not in a very bad area. Your angina is not very severe, and we can do a lot by increasing your medications and lifestyle changes. This is an excellent way to help you. And doing anything invasive isn't going to make you live longer, and I can tell you without question that many patients prefer to have it fixed. There's almost a feeling that it's like a cancer-- get rid of it, get rid of that stenosis. It's a time bomb. And, in fact, often that's misguided. Often we do it to meet the referring physician's expectations. We are frequently influenced by the notion that we want to avoid regretting, that an error of omission would be a terrible thing, particularly in younger patients. And so we want to do something. Action is better than inaction. Although, I would argue that aggressive pharmacologic intervention and lifestyle changes is certainly a lot of action. I think that we should certainly not be influenced by it winning lawsuits. We should do the right thing. There's a plethora of data to support doing the right thing. And, unfortunately, many of us continue to practice based on belief rather than being influenced by evidence-based medicine. And in the field of cardiovascular medicine in general and ischemic heart disease, there really is an enormous wealth of data that can guide us in many situations. And there may be other factors including financial ones. So I'm going to talk a little bit about the trials that have been conducted over the last few decades, evaluating the role of revascularization versus optimal medical therapy or guideline-directed medical therapy in patients with stable ischemic heart disease. Two of the very important trials have been the courage trial that was published almost 10 years ago in the New England Journal of Medicine and the BARI 2D trial. And what you can see here on the far left panel is when you look at optimal medical therapy depicted in yellow, as compared to PCI, certainly there was improvement in angina early on. But as you go out to five years, you can see that in patients who had optimal medical therapy, there was little difference compared to patients with PCI. Now, there are many people, particularly advocates for PCI, that will say that this data is dated, and it is true. It is dated. It is more than 10 years old, because the patients were enrolled even prior to when, of course, the study was published in 2007. And it was in the era of bare metal stents or first generation drug-alluding stents. And certainly our results are better now. But it's the data that we currently have, and it's one that we need to understand. And it should be part of the decision-making process. And if you look at the far right slide from the BARI 2 trial, you can see a similar type of phenomenon that in patients treated with medical therapy versus those with PCI that certainly had you gone out to your three, four, and beyond, that there is little difference in terms of the management of angina. And not only does that reflect the PCI has attrition over the years, restenosis and what have you, more progression of the disease in other vessels, but that medical therapy has become increasingly more effective in managing these patients. And what about the role of bypass surgery as an alternative revascularization to patients with stable ischemic heart disease. This slide shows two important studies that have looked at this. One is a very early study, the CABG trial, which was a collaborative study published more than two decades ago. And then the BARI 2D trial, which was a more recent trial that had both a PCI arm, that I showed you on the prior slide, and a bypass surgery slide. And what you can see is that, in general, bypass surgery does tend to have more success in reducing angina in patients with stable ischemic heart disease than medical therapy. And here [INAUDIBLE] up to five years, you see that the incidence of angina or a reduction of angina, freedom from angina in the medical group was significantly lower than surgery-- stating in another way that surgery is more effective. Similarly, in a more recent data set from the BARI 2D trial in patients that had adult onset diabetes mellitus, type 2 diabetes mellitus-- even in those patients you can see that all the way up to five years, surgery still conferred a benefit in terms of reducing symptoms of angina. So COURAGE and BARI 2D demonstrated high rates of achieving freedom from angina with modern intensive medical therapy. That's very important for us to remember, and should be the mainstay of treatment in all these patients. These rates were approximately twice the rates achieved in the no revascularization group in older trials, such as the CASS trial for surgery. COURAGE and BARI 2D showed that PCI initially results in improved rates of freedom from angina that tended to be less durable over time. And there's still speculation of why that may be. And bypass surgery tended to result in more durable, modestly improved rates of freedom from angina in patients over time. What about cost effectiveness of routine PCI or bypass surgery in optimally treated patients with stable ischemic heart disease. This slide summarizes data from both the COURAGE and BARI 2D trials. PCI had a cost of approximately five to $10,000 for patients, but no significant gain in life years or quality-adjusted life-years. Those are terms that are frequently used in cost effectiveness research. Lifetime cost-effectiveness projections showed that medical therapy was cost-effective compared with revascularization for the PCI group. And with high confidence, bypass surgery added approximately $20,000 to the CABG cost of managing patients, but lifetime projections suggest that revascularization may be cost-effective in the coronary artery bypass graft group, albeit at a cost of $47,000 per life year added. We generally consider things cost-effective if the cost of the added cost per life-year is less than 50,000. So it would achieve that goal. So shifting gears again now. What is the evidence that prompt revascularization after stable ischemic heart disease diagnosis improves survival and reduces clinical offence. We've talked about the role in reducing angina of different types of revascularization. But what about the, perhaps more important, longer term outcome, which is survival or serious adverse events, myocardial infarction and so forth. This is a meta-analysis that was published about a decade ago looking at the main randomized trials that had been published until that point and comparing PCI versus medicine. This meta-analysis actually predated the data from COURAGE and BARI 2D. And what you can see here is that when you look at PCI versus medical therapy, there really doesn't appear to be a strong signal that in any of these trial-- PCI improves outcome in stable ischemic heart disease. These are the key clinical events such as death or myocardial infarction. What about bypass surgery? This is a study that was published in Lancet more than two decades ago. And what this showed was that these trials demonstrated that bypass surgery did improve survival in certain subsets of patients. And so if you look at the main studies that were conducted at the time-- the VA study, European co-operative, and the CABG trial, and then did a meta-analysis that there was an increased survival, particularly in certain patients-- those who had left [INAUDIBLE] stenosis and patients with three vessel disease. However, one has to be careful in extrapolating more than 20 years later, because the relevance is unclear. For today, there was no use or minimal of the kind of effective medical therapy that we have today. In those days, we nearly didn't have Statin therapy or some of the more effective antiplatelet agents, or where there wasn't widespread use of ACE exhibitors. This takes me now to one of the pivotal trials that was conducted in the last decade or so-- the COURAGE trial, which was published in the New England Journal of Medicine about nine years ago. And this was a very important trial. It's been subject to a lot of criticism, both positive and negative criticism of almost 2300 patients with stable ischemic heart disease-- who were randomized to either optimal or guideline-directed, medical therapy or guideline-directed medical therapy in combination with PCI. This study was conducted mainly at VA hospitals in the United States-- primarily, including those patients and some sites in Canada. The primary endpoint was the endpoint we care about most in terms of outcomes, which is death or non-fatal myocardial infarction. And here you can see the money slide, if you will-- out to five years, there was no difference, no statistically-significant difference in the incidence of death or MI in patients who were treated with optimal medical therapy versus a combination of medical therapy and PCI. Following that, the BARI 2D trial was published a couple of years later-- very important trial for patients with type 2 diabetes. We know that we're having an epidemic of adult onset diabetes in the US, in many developing countries, and that this confers additional risk to patients with stable ischemic heart disease. And this trial randomized all 2400 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and stable ischemic heart disease to either prompt revascularization, [INAUDIBLE] guideline-directed medical therapy, or guideline-directed medical therapy alone. And if revascularization was going to help in any subset, one would expect it to help here. The primary endpoint in this study was it all caused death. And here again, you can see the money slide that up to five years-- if you look at patients with stable ischemic heart disease, all comers and concomitant diabetes, that there is no difference in the incidence of deaths with medical therapy versus revascularization. Remember, patients were revascularized with either bypass surgery or PCI, depending on the anatomic features and whether or not they were candidates for one type of revascularization or the other. This is a busy slide that basically looks at different studies that have primarily focused on cardiovascular mortality as an endpoint. This was compiled by Bangalore who is at NYU, a very good epidemiologic interventional cardiologist. And he looked at studies based on whether stents were employed or not-- whether they were drug-alluding stents or not. And what he showed in this meta-analysis is that when you combine all of these studies, and particularly the more recent studies, there does tend to be a strong signal that PCI may in fact favorably influence mortality in patients with stable ischemic heart disease. However, the caveat to this, as it is with any type of meta-analysis in not a true randomized trial is that there may be many confounding variables that we're not identifying that may explain some of the outcomes. So although the total number of patients was quite large in this and suggested that the signal was there, it really doesn't need to be corroborated by a large randomized trial before we can adopt this as our means to a treatment. Shifting gears now to this issue that I talked about earlier-- anatomic versus ischemia risk. What is really more important, whether a patient has a certain type of stenosis or in a certain location, or if it in fact induces ischemia as demonstrated perhaps by any of the tests that we use to demonstrate ischemia that I referred to earlier in the presentation? Well what we know from a number of studies is that moderate to severe ischemia is a marker for increased risk of death. However, it's unclear whether that increase risk of death is related to the adverse effects of ischemia, the fact that ischemia usually is a concomitant of a severe stenosis-- so that it's really the stenosis rather than the ischemia-- whether it's due to arrhythmia, or that perhaps more severe ischemia is a marker of a the large atherosclerotic burden and more vulnerable plaques-- which I explained earlier in the presentation, we believe are the precursors for potentially the more serious and life-threatening adverse events. This is an important study that was published from the group at Cedar-Sinai more than a decade ago. And what it showed was, using noninvasive myocardial profusion imaging, that in patients that have a greater amount of ischemia, a higher burden of ischemia based on myocardial profusion imaging, those that had minimal or none had a very low risk over the subsequent two years of cardiac death. However, in those in which there was more than 20% of the myocardium that was ischemic on studies had a much higher, almost tenfold, increased risk of dying over the subsequent two years. What they showed subsequently in another study is that, again, not a randomized trial, but in patients who we revascularized, there appeared to be a mitigation of the risk of death as compared to medical therapy. Again, not a randomized trial. But what this suggested and was hypothesis-generating, is that rather than looking at anatomy-- rather than look does a patient have one vessel disease, two vessel disease with stable angina-- what if we actually looked instead the amount of ischemia that was provoked by their disease. Perhaps if we, in fact, selected those patients out, those are the type of patients that would benefit by revascularization more than optimal medical therapy. Particularly the burden of ischemia was moderate or severe because the studies I showed you previously really were looking at anatomic features of Artery Disease rather than whether or not there was ischemia. And, in fact, because of these provocative ideas, there have been some looks back at a number of the studies that were negative in terms of revascularization. In the COURAGE Trial, there was a nuclear sub-study. And what the sub-study suggested is that patients who have a lot of ischemia, that the combination of revascularization with optimal medical therapy did, in fact, lead to an improvement in patients' outcomes and survival. So the COURAGE nuclear sub-study looked at the outcomes in 05 patients who had demonstrable moderate to severe ischemia baseline. And what it showed was the PCI did reduce ischemia when you looked at their paired nuclear profusion study at 6 to 18 months. And that reduction in ischemia was associated with fewer events. So, again, small study. It was a sub-study. But very thought-provoking. Subsequent to that, there's been additional type of data that suggests that we should be looking more to ischemia as a marker of risk than anatomic features. And many of you may be familiar with Fractional Flow Reserve. It's a technology that we've adopted in the cath labs over the last decade. This is a way to actually demonstrate whether or not there's ischemia for a given lesion. So Fractional Flow Reserve is also known as FFR, that's the acronym. And this study-- the same trial, very important study-- was published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2012. And it was a study that actually randomized patients who had a stenosis, an anatomic lesion. And it randomized them according to whether or not the FFR suggested there was ischemia or not. So if the FFR was less than 0.8-- that was the cutoff point-- they were then randomized to optimal medical therapy or revascularization with optimal medical therapy. So, in other words, patients who had ischemia. And then they had a nested registry of patients in that study who did not demonstrate ischemia. They had anatomic lesions, but the FFR was not abnormal enough to suggest that there was important ischemia. And they followed these patients for two years. And very importantly, what they found is that in the patients who had optimal medical therapy only and had demonstrable ischemia, they, by FFR, had a much higher risk of an event-- death, MI, or revascularization-- than the patients who were treated with revascularization. Here you see in the Kaplan-Meier survival curve that the primary endpoint of all caused death, MI, or urgent revasculariation. And then you can see here that in the patients who had medical therapy alone, there was a much higher incidence of the combined endpoint. Again, remember, these are patients who have demonstrable ischemia. So this, in fact, may be based on the same too, in other trials, really, the direction we should be going in terms of identifying patients who will benefit by early revascularization. So what do we really know now after the FAME 2 trial? An analysis of it suggests that we can't really extrapolate the state to all patients because it was performed after cath. Really, when we're looking at patients who have angina or stable ischemic heart disease, these are outpatients or clinic patients. And we're trying to determine who of these patients-- or, which of these patients should be going on to revascularization early? Or in whom is it safe to continue with guideline-directed medical therapy? Other issues were that if the primary endpoint of COURAGE and BARI 2D were included in the revascularization procedures, there would have been a significant difference between the arms. But there was no difference in death or MI. And they did not really indicate the success of medical therapy or risk factor control in these patients. So this brings me to the next important trial, which was a trial comparing and looking at different modes of revascularization in the modern era of drug eluting stents and bypass surgery. This is the SYNTAX Trial, which was published about six or seven years ago in The New England Journal of Medicine. This was a trial that randomized over 3,000 patients mainly in Europe and in some US centers to either bypass surgery or PCI. Many important outcomes from the trial included our ability to score in a more systematic way the severity and complexity of Coronary Artery Disease, which led to the so-called SYNTAX Score, which is available online and which I really do strongly suggest that we apply many of our patients in whom we're trying to decide whether or not they should have PCI or bypass surgery. And the important outcome of the SYNTAX Trial at five years-- here you see that for that combined endpoint, that overall, bypass surgery won. Although, it was mainly due to the increased rate of revascularization-- the need to have repeat procedures with PCI as compared to bypass surgery. Importantly, if you look at the outcome of the trial at five years by the Syntax Score, and a higher SYNTAX Score means more complex disease, longer lesions, more lesions, more vessels involved. And what you see here is that with a relatively low SYNTAX Score, even Multi-vessel Disease-- all these patients had Multi-vessel Disease-- but it's relatively low score, meaning more focal lesions, lesions in less branches. But bypass surgery and PCI were very comparable. However, as you progressively look at subgroups of patients with more complex disease, meaning longer lesions, more diffused disease, surgery, and this study clearly had an edge. I'll move forward here for the sake of time. Very importantly, we learned a lot about management of Left Main Disease. Left Main Disease is generally considered an anatomic lesion that almost always should undergo revascularization, not treated with only guideline-directed medical therapy. And we found something very counter-intuitive. We found that in most patients with Left Main Disease, the PCI and surgery had similar outcomes at five years, even for patients up to intermediate complexity, so-called SYNTAX Scores of up to 32. It was only in the patients that had, in addition to the Left Main, diffused or complex disease in the other vessels that surgery was superior. And this, in fact, has finally percolated through to the guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and other societies, in which now Left Main Disease is a very appropriate and bonafide lesion to treat by PCI so long as it's associated with relatively uncomplicated disease in the other vessels. Or if it involves primarily the proximal and mid portion of the Left Main coronary artery rather than the bifurcation. I'm going to shift now to the FREEDOM Trial, which was one of the last important randomized trials published regarding the role of revascularization versus guideline-directed directed therapies, Stable Ischemic Heart Disease. The FREEDOM Trial particularly looked at patients with diabetus mellitus and what the optimal management ought to be. And it randomized 1900 patients with diabetus and Multi-vessel Coronary Artery Disease who were eligible for either PCI or bypass surgery. So anatomically, a surgeon and interventional cardiologist felt that they could have either. And they were randomized 1:1 to PCI versus bypass surgery. And they were all, as I mentioned, on optimal medical therapy. And, importantly, what this showed at five years is that the rate of the important outcomes-- average outcomes-- was higher again with PCI than bypass surgery. We, for many years, felt that patients with diabetus mellitus, in general, fare more favorably if they undergo bypass surgery than PCI. And the FREEDOM trial really strongly supports this, even in the more modern era, with drug-eluting stents. What about patients with bad ventricular functions-- ejection fractions under 35%. Well, the very important STITCH Trial showed, in general, that the patients with bypass surgery in the overall trial did not confer benefit. But in teasing out ischemic versus non-ischemic patients, you would have expected, perhaps, that if there was ischemia, that the patients would do better because it would suggest there was more viable myocardium. But unfortunately, there was no difference in the survival curves in patients who had ischemia or not in the STITCH Trial. This slide summarizes some of the concerns that we have regarding the types of biases when we refer patients for revascularization, including the prior trials COURAGE and BARI 2D. And that if we really want to have data that will help us or guide us in terms of how to refer patients with Stable Ischemic heart Disease for revascularization, we really need to move the decision making earlier in the process. Mainly in patients, for example, who have not yet had cardiac catheterization. And to that end, the National Institute of Health in collaboration with a number of investigators in the US, designed the ISCHEMIA Trial, which is an international trial, to look at the comparative effectiveness of optimal medical therapy versus invasive approaches. It's currently under way. In this trial, the hypothesis is that an initial invasive strategy of cath and optimal revascularization, depending on the patient's anatomy, plus the guideline-directed medical therapy is superior to the conservative strategy of optimal medical therapy alone. In which a cath would be reserved only if the patient had a breakthrough angina or symptoms, despite optimal medical therapy. It was powered appropriately with 8,000 patients. It's still ongoing. And we did participate early in the trial. Very, very hard to enroll patients in this trial. I'm going to now quickly end up with the most recent guidelines from the Main Society, the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the surgical societies. Initially, this was published in 2012 with a relatively small, focused update in 2014. And I'm going to go through some of the key issues. So what should be the algorithm for risk assessment of patients with Stable Ischemic Heart Disease? And if we know that they have Ischemic Heart Disease, how do we really determine their risk? If they're able to exercise and they have a reasonable electric cardiogram, then doing an exercise test should be the standard. We shouldn't be putting all of these folks through pharmacologic stress testing. If they're not able to exercise, then that's the primary indication for using pharmacologic stress. And this goes on to show what our algorithm should be based on the results of the test. If the tests show high risk lesions, mainly significant ischemia, that we should consider coronary angiography and potentially revascularization. There's no role for doing coronary angiography, generally speaking, unless we really plan to revascularize. If the patient says, I'm not going to have PCI, and I'm not going to have surgery under any circumstance, then, really, we shouldn't be subjecting these patients to invasive studies. So based on this algorithm, and you may be familiar with the guidelines from the societies-- generally use a type of scoring system where one going from one, which is indicated. All the way to three which is not indicated and potentially deleterious. And then also discusses the type of evidence. So A is EV, excellent evidence based on randomized trials and then all the way down to evidence that may just be based on expert opinions. And here you see that coronary angiography is an initial testing strategy to assess risk. And patients who survive sudden death or life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias get a 1B indication. That's who should get an angiogram. Patients with Stable Ischemic Heart Disease who develop symptoms and signs of heart failure, also very serious. And these patients have a Class One indication. Patients who have Stable Ischemic Heart Disease and their noninvasive testing suggests a lot of ischemia. As we've shown in some of the prior slides about the risk of that, again, a Class One indication. Patients who have Stable Ischemic Heart Disease with depressed ventricular function and moderate risk on non-invasive testing, we know that those two characteristics are serious. Although it doesn't get a Class 1 One. It gets Class 2A, which means that it's generally reasonable to cath these patients. Coronary angiography is reasonable to further assess patients with a Stable Ischemic Heart Disease in which the non-invasive testing was inconclusive. Also in patients who have unsatisfactory quality of life due to angina and reserved ventricular function with intermediate risk, they also get a 2A, which means it's reasonable. Patients who elect not to undergo revascularization, as I indicated, should not be cathed. So they get a Class 3 indication. It's also not indicated or recommended for patients who have preserved left ventricular function and have a low risk stress test. Coronary angiography is not recommended to assess risk in patients who are low risk based on clinical criteria and even if they haven't had noninvasive testing. So you shouldn't go just from the office to heart cath if the patients have symptoms, but they're generally at low risk. Unless you can prove that they're at a higher risk with noninvasive testing. It's also not indicated in asymptomatic patients who have no ischemia. That obviously stands to reason. I'm going to go through some of these slides for the sake of time. And I'm going to end up really with this last slide, which is a pretty busy slide. And this is, again, from the most recent guidelines suggesting when to do revascularization. And what you can see here is that it's divided up according to the American guidelines. And then you have the European guidelines. And I think it's pretty obvious that we're a lot more complicated in our recommendations in the US as compared to the European Society of Cardiology. But going through the American recommendations, you can see here that in general, we recommend revascularization for Left Main Disease. Bypass surgery gets a Class 1 indication. PCI, depending on the anatomy, gets a reasonable to a recommendation. But for higher SYNTAX Scores, for example, they should not advise PCI for Left Main Disease. It should be bypass surgery. Three vessel disease gets a Class One indication for bypass surgery, but not so much so for PCI. Two vessel disease with the proximal LAD-- so a particularly high risk category of two vessel disease-- again, gets a Class One indication for bypass surgery. Two vessel disease without proximal LAD disease, usually the recommendation can be optimal medical therapy. Again, depending on risk that can be ascertained from noninvasive testing. In this case, it gets a reasonable Class 2A for bypass surgery. And generally not something we should be doing a PCI. One vessel disease with proximal LAD involvement is reasonable to do bypass surgery if there are high risk features on noninvasive testing. One vessel disease without proximal LAD disease-- so if you have just one vessel disease and it's not proximal-- generally the guidelines suggest that these patients should be treated with medical therapy. They don't get much benefit by undergoing bypass surgery or PCI in terms of survival. And, really, the indication for revascularization is if they have uncontrollable symptoms despite best medical therapy. Left ventricular dysfunction is very important as a marker, in terms of determining whether to have revascularization and which type. And in general, if patients have left ventricular dysfunction that's significant in EF of under 35%, we tend to favor bypass surgery over PCI. And then, of if the patients have unacceptable angina, then doing revascularization either by PCI or bypass surgery tends to be reasonable. And I'll finish here. Thank you. We finished a little bit late, so perhaps we'll just take a few minutes for questions. Any questions? SPEAKER 2: [INAUDIBLE]. A really great talk. One question I had is that with some of the new technology [INAUDIBLE]. For example, even some neuroendocrine approaches, too. [INAUDIBLE] Which may relate to [INAUDIBLE] control of angina with Coronary Artery Disease, you see that these may change these processes of Stable Disease. SPEAKER 1: So, certainly there's a great hope amongst interventional cardiologists and other practitioners that some of the more recent advances in technology, particularly bioabsorbabal stents of different types, more extensive revascularization might, in fact, alter the risk-benefit profile of doing percutaneous intervention. I think we've learned a great deal of the role of surgery. And we know that surgery has a significant, long-term benefit in terms of symptom control and survival in very specific subgroups. But the hope is with some of these advances that we may see longer-term benefits with PCI. But those studies aren't completed yet. And I think there's a lot of interest in conducting new, randomized trials. Obviously, they're expensive and requires both industry, and potentially, federal support. Other questions? I think we'll end here because it's pretty late. Thank you all for your attention. Don't forget to fill out your forms if you want CME or CNE credit. Thanks so much.